“Work on, age after age, nothing is to be lost,It may have to wait long, but it will certainly come in use,When the materials are all prepared and ready, the architects shall appear.“

-Walt Whitman

There is a line from Leaves of Grass that has followed me for over 20 years in my work of trying to put all the pieces together to build something big: When the materials are ready, the architect shall appear. I used to think of it as a beautiful idea about timing and fate, but the older I get, the more I realize it is actually about work. It is about years of quiet preparation that no one sees. It is about building a foundation strong enough that when the architect shows up, he or she is not creating something out of thin air but designing something that already has weight and form.

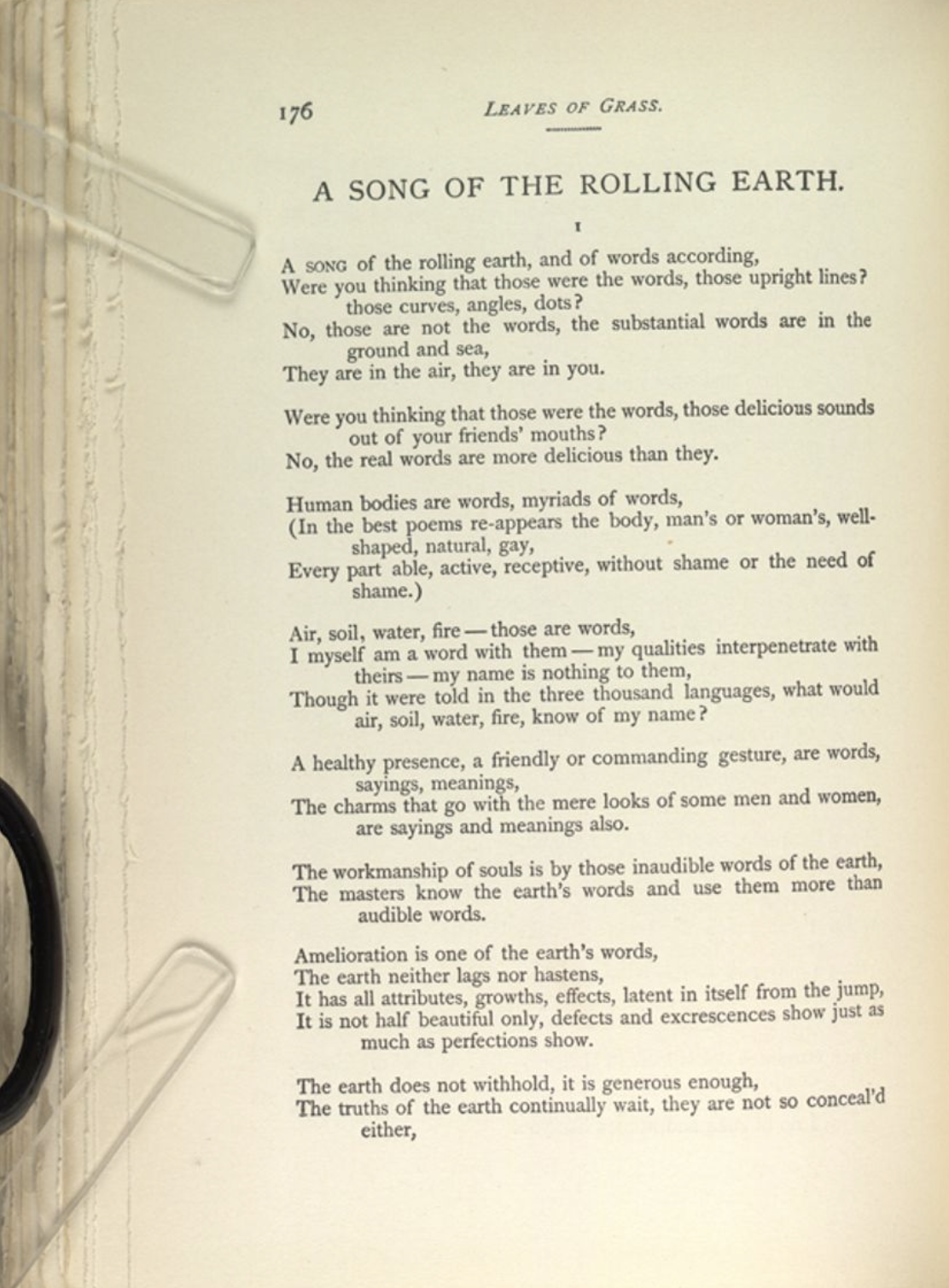

I have been thinking about that line a lot as we enter this next phase of Excelsa. For the past few years we have been the materials. My business partner and I put in significant capital of our own (relative to us). Not promises. Actual capital. We spent years working without paying ourselves a salary. We lived inside the uncertainty of it and carried the whole thing on our own backs because we believed the idea deserved time to mature before we asked anyone else to believe in it. We took over a building we own outright and let the idea take up space on our own square footage and our own farm lease in Nicaragua where we planted 1,500 trees. That building and farm became our first proof of permanence, the physical sign that we were serious. Including our own café next door (The USA’s first excelsa cafe). We built and rebuilt our identity, our domains, our product, our supply chain, our story. We moved quickly and early to secure the IP and the brand so that when someone one day looked at what we were doing, they would see more than another bag of arabica coffee. They would see the beginning of a climate resilient, future sustainable species, coffee category.

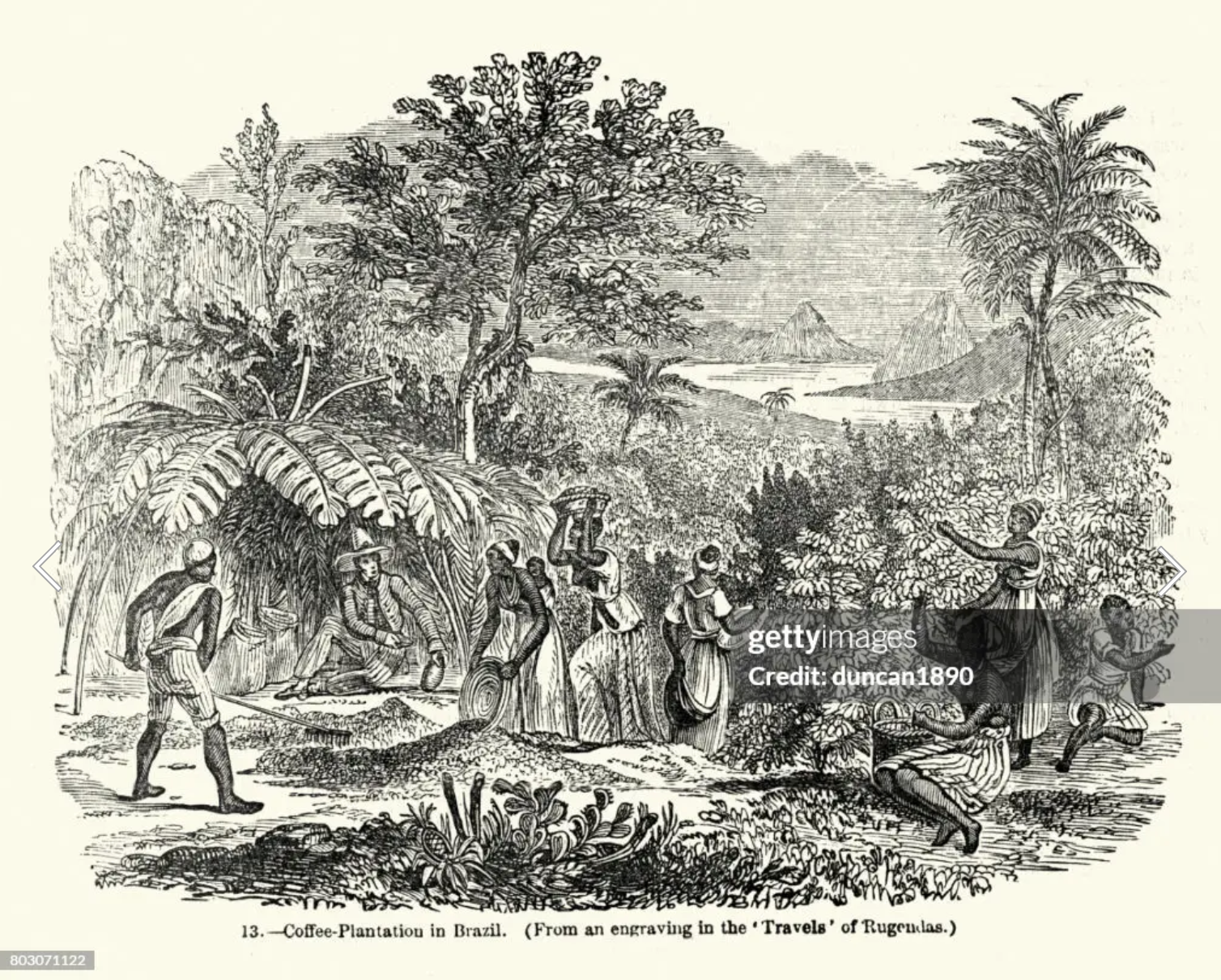

Most people do not realize how much of company building happens in those early, quiet years. It is not glamorous (it sucked and hurt). It is not loud. It is not something you post about. It is painful conversations with my wife about why we need to risk more capital towards something so risky, its spreadsheets and freight quotes and redoing packaging, and figuring out cost of goods, and finding suppliers (and planting our own), and building relationships across oceans. It is decisions that feel small but are actually massive because they set the tone for everything that follows. All of that becomes the materials. All of that is the readiness that Whitman was talking about.

That is why standard revenue multiples do not really apply here. That is not what this is. This is not a traditional business model. This is not a brand extension. This is not a product sitting on a shelf waiting for foot traffic. This is category creation for those with the risk appetite to believe it before anyone else does. And category creation is valued on two things. The true cost of becoming meaningful in the space. And the upside if the category works.

The cost part is simple reality. I have managed budgets for some of the biggest CPG companies in the country. I know what it takes to make something real in this world. I know the cost of freight and co packing, SG&A, and marketing and certifications and supply chain teams and logistics and distribution and sampling and compliance. You cannot do this with small numbers. You cannot build a vertically integrated supply chain with discount capital. The valuation is not inflated. It is honest. It reflects the actual scale required to matter and the capital required to hit that scale.

The second part is the asymmetry of the upside. If this works, it changes the landscape of the entire coffee industry (the world’s most consumed drink except water). If this works, it introduces a new species into one of the largest beverage markets in the world (a multi-billion dollar space). If this works, it is not a slow climb. It is a leap. Investors who understand that kind of opportunity do not ask for last year’s revenue. They ask what the world looks like when this catches. They understand that category creation is one of the most powerful sources of upside in consumer packaged goods. They understand that the real risk is not the valuation. The real risk is missing the one chance to be early on the these rare once in a decade opportunities.

So here we are at the moment I have always dreamed about. Finding the right partners. Not money for the sake of money. But smart capital. People who understand this industry. People who know how to build something from the ground up. People who have the experience to look at what we have already done and say yes, the materials are ready. People who can bring something equal to or greater than capital itself. Judgment. Insight. Operational knowledge. A sense of timing. A sense of scale. People who know how rare it is to get in early on a category that has a chance to reshape the way people drink coffee for decades.

This is the first real round. It might be friends and family. It might be operators. It might be people in the coffee world. It might be early believers who see what is coming before it arrives. I am reaching out widely. I am practicing the pitch. I am getting sharper and more clear every day. I am learning which parts resonate and which parts need to be reframed. I am putting Excelsa onto the radar of people who think deeply about consumer behavior and global supply chains. This is work I love. It is not intimidating to me. It is energizing. I like the responsibility of it. I like the clarity required to ask someone to trust you. I like the discipline of organizing a story that can carry the weight of real conviction.

There is also the piece people do not talk about enough. The desire to build a company where every stakeholder wins. Customers. Workers. Farmers. Suppliers. Investors. There is something deeply meaningful about building something that can deliver value on all sides. Something that can be financially healthy and structurally sound and spiritually aligned. A company that honors the craft of coffee, the dignity of the supply chain, the beauty of the product, and the responsibility of stewarding someone else’s capital. That is part of the mastery. That is part of the reason I am excited for this stage. For the chance to prove that a company can be generous, efficient, profitable, world changing, and deeply rooted at the same time.

The last piece is patience. Not passive patience. Not waiting around. The patience that comes from understanding how long this takes. Two or three years before the capital we raise even starts to show its full effect. Time for the farms. Time for the supply chain. Time for distribution. Time for consumers to recognize something new. Time for the slow work that has to be done if you want the result to last. We have to move quickly because the market is coming. But we also cannot force the river. We have to trust the seasons. We have to trust the pace of real buildout. We have to trust that what takes time is worth it.

So I come back again to Whitman. When the materials are ready, the architect shall appear. That line feels like the truest way to describe where we are now. We have put in the work. We have done the part no one sees. We have built something substantial enough that the right people will feel it when they look at it. The materials are ready. The foundation is here. The story is coherent and alive and urgent.

Now we trust the universe.

Now we trust the work.

Now we trust that the right partners will recognize what we have built and bring the next layer of design to life.

This is the part of the journey I have dreamed about.

And now it is here.

When the materials are ready, the architect appears.