A 10 Year Road to The Nose of El Capitan

In 2013 I went on a backpacking trip with my sister to Yosemite Valley. It was a rare snowless winter and we slept feet from the cliff’s edge on top of Yosemite Falls. We had uninterrupted views of El Capitan, Middle Cathedral, and Half Dome. It was the first time I saw people climbing Yosemite walls. I had no idea people climbed those walls. It was a perplexing observation to witness. It was so far outside of anything that I could comprehend. I saw what an adventure climbing was.

Later that summer, I was in Las Vegas at an annual co-workers’ party weekend. A coworker Greg had just climbed the Nose (the central prowl up El Capitan) in a day. I was enthralled and wanted to know more. I switched cars on the ride home to talk to him. The entire four hour drive he explained lead climbing, trad climbing, hauling. I can’t say I understood much but I asked questions the entire way – how do you poop? How do you get the rope up there? What do you mean they failed? Did they die? That week he gave me his old climbing rope. I was honored by the gift.

My start with climbing was rough.

Greg invited me to climb a few weeks later and within an hour he had to drive me to the JOSAR (Joshua Tree Search and Rescue) HQ to tend to a cut I had from falling that was bleeding out of control. A month later I’d try my first multi-pitch on Mammoth Lake’s Crystal Crag, leaving way too late in the day and with no headlamp or emergency gear. We summited after the sun had set, exhausted and disoriented. My climbing partner and I sat there on a ledge 20 feet shy of the summit spooning each other in the cold at 10,000 feet above sea level. We shivered like crazy until the sun came up the next morning. I remember my butt cheeks were so cold. I remember counting the minutes till sunrise. 90 minutes before sunrise was the absolute lowest point. We bailed at first light and slept most of the day in the parking lot.

The next climbing trip nearly put and end to the entire thing. The first pitch of the first day with a new partner Mattie, I whipped (fell) 50 feet off Joshua Tree’s Right On, cheese grading the low angle slab wall the entire way down. As I hung there on my lead line turned top rope (just a few feet from having hit the ground), hands bloody, pants ripped, down jacket shedding goose feathers into the wind, I knew there was a choice I had to make. Be lowered down, go back to the car, drive home, never climb again, or get back on the horse. In that moment I wanted the former. I swallowed my pride, my hurt body, and my bruised ego and went for the latter. I got back up there and got it done. Joshua Tree grade 5.5 baby.

Over the next couple years, my pursuit of climbing opened an entirely new world for me. I took a job at an outdoor retailer called Gear Coop. I began accumulating climbing gear, I met professional climbers and got to hang with them (I stupidly free soloed behind Ethan Pringle up Joshua Tree’s The Eye in sneakers and nearly killed myself), I went to Greece with the Dawn Wall Climbing Hero Kevin Jorgeson. I attended film premiers with climbing legends Conrad Anker, Alex Honnold, Renan Ozturk and Jimmy Chin. I met and befriended incredible artists like Cheyne Lempe who produced compelling videos and photography about big wall adventures.

Without thinking about it, I started climbing routes that would be considered part of the checklist for climbing something like El Capitan. After a failed attempt, Mattie and I successfully climbed Zion’s Moonlight Buttress in 1.5 days. I had other wall experiences like Middle Cathedral and Half Dome. I rope soloed in Tahquitz, and practiced hook moves (delicate aiding) on the lower pitches of El Capitan’s Pacific Ocean Wall. I put in long days climbing in Tuolumne and Red Rock with Mattie. There were so many incredible crag days in the Valley on Manure Pile, Glacier Point Apron, Snake Dike and more. I had picked up backcountry skiing and mountaineering too – skiing summits like Mt. Shasta, Pico De Orizaba, and Austria’s tallest mountain the GlossGlockner (in Mattie’s home country), which required a 500 ft simul-climb to the summit. My curiosity of climbing had opened so many doors to a world of endless adventure.

But in the back of mind there was always that memory of camping on top of Yosemite Falls with my sister and that chat with Greg in Las Vegas about the big challenges that were out there. Was I or could I be capable of climbing something like El Capitan?

In Yosemite Valley, there is a parking lot called Valley View while exiting the park. From its vantage looking back into the value, El Capitan appears to emerge so tall and so vertically out of the creek shores. It’s a famous vantage that everyone would recognize as millions have snapped a photo here and many famous painters like Thomas Hill stood on that shore creating their masterpieces. But it’s also a stark visual reminder of how wild the monolith of El Capitan is.

Right in the middle of over developed California, in a crowded valley, there is a 3,000 foot vertical wall that rises from the parking lot, the prowl of it (called The Nose) presenting arguably the most exposed and outrageous climbing route right up the face. I had traveled the world and nothing I had seen was of such juxtapose. A grand adventure, so outrageous, but a 15 minute walk from the parking lot. Most walls of this nature require month long voyages to faraway places like Baffin Island. After every successful visit to Yosemite, I would stop in that little parking lot. The dream of climbing El Cap would take root.

The pandemic came and was a disastrous time for me. I publicly embarrassed myself tanking a company I had due to covid’s supply chain issues. Two years had gone by. I was out of shape, and hadn’t had any adventures as I struggled through the lockdown. I felt lost and directionless. Ideas like climbing big objectives seemed behind me now. And to add pressure to the situation my wife was pregnant. We were expecting our first child early the following year (which was a joy) but it felt like a window was rapidly closing on a period of my life that was meant for achieving big adventures.

Agreeing that the best thing for my mental health was to take some time off work (we were broke but my work was making us broker) my wife agreed just to let me take some time to get my head right. I decided to work out every day. I ate corn tortillas for every meal and we lived off her teacher salary. Working up first physically to have the stamina, but then spending hours a day swimming in La Jolla Cove and running Mission Trails nearby. Three months in I had lost 20 pounds, and was arguably in some of the best shape I had been in in a long time. One afternoon I received a call out of the blue from a friend named Jake, “I’ve always wanted to go climb El Cap, let’s go” he said.

Jake is a friend that I had been on many adventures with through the years. We had skied Hotlum Bolam Glacier on Mt. Shasta, had a wild 24 hour bender skiing Snow Creek on San Jacinto, and a radical trip to Mexico to ski Pico de Orizaba (North America’s tallest volcano). We had suffered together, triumphed together, been nearly arrested together, and most importantly Jake was someone I considered a friend, mentor and inspiration. Jake could have easily been a professional athlete the way he moves with such fluidity in the mountains. But I also know that would have squashed his love for the wildness of being outdoors. Jake is a wild man.

Needless to say, I was honored by his phone call invite. But I was hesitant. Thank God I had gotten myself in shape but I hadn’t climbed in 2 years, AND more importantly, on principle, I needed personally to be at least a 50% contributing member to this effort. Partially for both of our safety (I didn’t want to not be able to be there for him, nor get myself in jeopardy if something were to happen to him), and for the sake of achieving the goal of climbing El Cap wanted to know I was not handed the summit by some guided tour. If I couldn’t hold my own, I would have no business being there.

After voicing my concerns, I started feeling better that we would make the unlikely duo of what it takes to pull off climbing El Cap. Jake was a strong lead climber, and I (at least convincing myself) had the stamina and would take the technical aid leads, work systems, and be the workhorse with hauling, et al. Jake had not ‘big wall’ climbed (mostly due to the fact he is such a fast climber he doesn’t have to spend the night on a wall). I had the big wall stuff somewhat down, so together we’d be a diverse team with the mix bag of tricks required to take on the challenges of climbing the Nose of El Cap.

Attempt #1

Strategy: Beat the Crowds.

A couple weeks later in mid-fall we were driving north on the interstate 5 from Southern California towards the Valley. It had been a stormy week, with perfect weather in the forecast for the foreseeable future. The Nose is infamously traffic jammed, and it was prime climbing season. So our fears of traffic jams and lines to climb inspired us to cast off as soon as the rain stopped, no matter what time it was.

We arrived in the late afternoon just as the rain let off. We went straight to the meadow parking lot, threw everything haphazardly in a mad dash, unsure of really how much water, food, or gear we had. We set off for the 15 minute walk to the base of the route. We feared an army of climbers would arrive by 4am the next day, so we had the head start we needed.

It was important to me that I set the precedent that I was going to carry the load with Jake as an equal partner, specifically with the heady lead climbing (for me it would be mostly aid though). The first 700 feet to Sickle Ledge (the first major ledge on the wall) are considered some of the most challenging because of their mandatory mixed climbing of aid and free. I assured Jake, I had this. He would then be free to fire the next 700 feet above of perfect splitter hand crack and gain back time by climbing free style. I’d get us to Sickle by midnight, I assured him.

As I cast off into the nearly dark sky up the first pitch called the Pine Line (technically it isn’t the first pitch as there is an easier but less direct route to get to the base of the nose another 200 feet above us), I was perplexed at how hard of a time I was having pulling on 5.7 Yosemite flared cracks. Oh boy I thought, my anxiety hitting me hard. Did I really just convince myself and Jake that I could do this, and thereby waste his time by driving 400 miles to get here, and take a week off of work? I pushed on past the two pitches of Pine Line into the actual start of the Nose.

Things turned dicey for me quickly. From there the flared crack with pin scars I was forced to aid through was soaking wet with moss and water, turning the polished rock to as slippery as soap from the storms that had just passed. I struggled committing to the mandatory free climbing transition another 100 feet up. It was getting late, and my head was starting to spin. I did the unthinkable, and asked to be lowered down. Upon reaching the belay station to recalibrate, Jake had jugged the line I put up with a fixed traction device in his harness starting a conversation about how our tactics were gonna go for the next 3,000 feet. And out of nowhere, a team rappelled onto us on 3mm double ropes, which somehow caused the apocalypse of tangles all around us. By the time they were untangled and reorganized, it was nearing midnight. We were a dismal 200 feet up the 3,000 foot face and exhausted. This attempt had been a failure. We decided to retreat, get aligned on strategies, rethink what we packed, and give it another go tomorrow.

Attempt #2

Strategy: Go light, Go fast.

The obvious path to success on The Nose, is to go light so you can go fast. Bring excess water and food, and you burn out carrying it all. Or so we thought.

The next day we resented how hard it was to haul so much food and water to the base of the climb and up the first few pitches. If we were going to be successful, we were going to have to bring less water. What we failed to understand was that the temperatures in the Valley and on the Nose, would be 20 degrees warmer than the day before. Jake took the leads on the pitches to Sickle, climbing in great form, and yarding what he could for lost time. It was hard climbing, and by the time we made it to Sickle Ledge that afternoon, we had drank half our water. There is no way we are going to make it the remaining 2,400 feet with the warming dry weather and remaining climb. Shit, we thought 700 feet up the wall, we need to bail to go get more water.

Attempt #3

Strategy: Burn it down, we are going home

The next day, we set off later in the day with the plan of just making it to Sickle, so we could embark on the rest of the climb at 4am the following day. We went to the Yosemite Mountain Shop in the Valley to pick up a few supplies, grabbed food and water and started out on our third quest for glory. I felt tired and stressed. Things felt like they weren’t clicking for us. I felt insecure about my abilities to do this. El Cap puts a doom and gloom on one’s psyche and I hadn’t slept well the past couple weeks because of it. It was hard to comprehend what we were in for in the days to come.

We headed off for the wall with extra food, gear and water. Hoping this time we had what we needed for success. On those first 700 feet for a third time, a frustrating situation of infinite magnitude went down. While Jake was powering ahead of me a couple hundred feet, I was below hauling the bag up to our first anchor. I stupidly didn’t coordinate a clean release of the bag, and it all got wedged into a boulder on the ground. The whole ordeal took me over an hour to fix having to descend and re-ascend, and I was FRIED. By the time I had it fixed, and hauled those 700 feet, and got back to Sickle with our gear, my rage, exhaustion and fear had gotten the best of me. We were hungry, tired, sunburned, and for the third time had only made it to Sickle. El Cap was shutting us down.

Fuck it I told Jake, profusely apologizing for the mishap and wasting his time. Let’s burn it all down and go home, this is just too much. We agreed that we would sleep on Sickle, throw a huge party with the excess food and water we had just hauled (and rationed all day), get a great night of sleep, and head down the next morning and go home. DONE, Jake agreed. His vacation time was ending in a couple days anyway, and we were nowhere near where we needed to be so he could be home in time.

We ripped through the food, we slammed the water. We cooked a warm meal on the JetBoil and listened to music and Thich Nhat Hahn poetry on Jake’s iPhone. It was a glorious evening, and one I will never forget. As our bellies were full, we laid on our portaledge, looking down at the incredible view below and up at El Cap’s 2,400 foot face above us. I was not even sure I would ever be back here again. We dozed off sometime around 9pm.

During the night, I would go in and out of sleep, awaking to the bowl of a billion stars above us. To the ominous and powerful wall as it leaned over our tiny ledge. I felt the expansiveness of the universe in a way I had only ever felt when I was sleeping on a portaledge. I felt like a tiny, meaningless speck. I felt completely insignificant. I was in awe. I could hear Jake rumbling next to me on our tiny ledge as well. I wondered what he was thinking.

I awoke pretty early the next morning. An hour or so before first light. Orion had slid across the night sky. I felt calm and full. At that moment I realized the gravity of our situation. We were healthy, uninjured. The weather was great, the crowds were non-existent. I had a pregnant wife at home with an endless list of tasks to prepare for the coming baby she would be throwing my way. I knew if we left now, I would have left something on the table. I knew I’d regret it, and I knew I might not get the chance to be back.

I heard Jake awake. I started to share my thoughts. I told him, we’d had a rough go. Mistakes had been made. But I also pointed out we’d been nothing but rushing since the moment we arrived at the Valley several days back.

I said what if we just went to the Valley floor today. You take some more vacation days off. We chill by the river, we shower and wash our clothes. We sit in the Valley, play guitar and sing. Practice any techniques that need review. We eat a giant cheeseburger. We then come up in the evening, leave our stuff here, sleep again and then fire this thing.

Jake agreed to it all. It was on.

The day ahead we did all those things and it was glorious. When we came back to the wall nearly 12 hours later, I felt strong, ready, committed. Jake looked those things too, but Jake always looks that way. We were back at Sickle, feeling transformed and headed to bed early for an early wake up tomorrow.

Attempt #4

The Send.

4am wake up. Jake takes the lead up past Sickle as I clean up camp and belay him. We are quick to gain the Stove Leg cracks, finding the pendulums into them fun and challenging both as leader and follower. The expanse of the wall really starts to set in, the sea of granite envelops us. We are really getting up here I think to myself. Jake puts in a huge day on the sharp end of the rope, climbing up the 700 feet of insane splitter crack. We pass Dolt Tower and are at El Cap Tower by sunset. We arrived alone on the largest ledge on El Cap, and my God it was incredible. A perfect day, with Jake putting in most of the leg work to break our spell and get us on our way. That night we ate a warm meal. We even FaceTimed back home keeping it brief to save precious battery. But we finally had news worth sharing and it deserved a celebration. Tomorrow would be my big day to put the lead work in, and get us set up for Camp 5, so we can summit the following evening.

That night as I lay on the ledge, I realized that the following day I would face so many adventures that I had spent years dreaming about. The precarious stance and cast off from the Texas Flake. Climbing the Boot Flake, infamous for not being connected to the wall, and one day surely falling off (hopefully not while I’m standing on it). Doing the massive King Swing to gain a necessary new crack system to make further progress. Climbing under the outrageous Great Roof, with 2,000 feet of exposure beneath and a crack system no wider than a pinky finger to traverse from underneath its roof. Tomorrow will be one of the best days of my life. I laid in bed thinking.

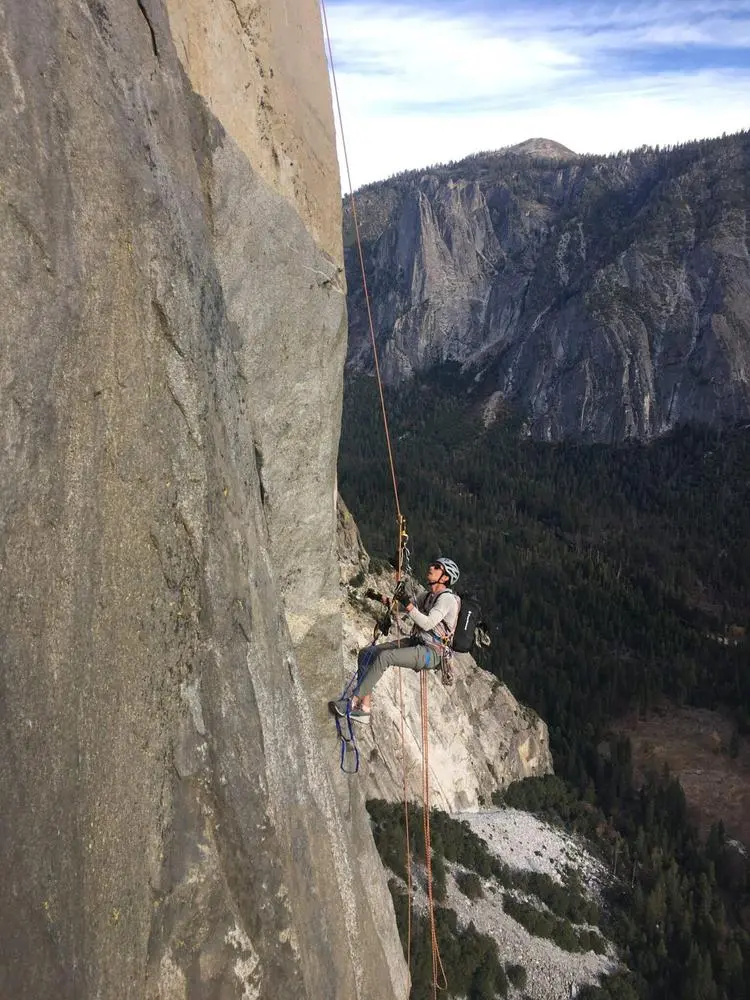

The following morning we were off, with my turn to take charge and unlock the adventures to come. As the day progressed it was everything I dreamed. I lead the Boot Flake pitch, lead the massive King Swing, gaining 50-60 feet of airtime in a big pendulum. My climbing was mostly aid, so progress was slow, and Jake did step in to lead a few pitches. By sunset we were under the Great Roof. A daunting site to behold. 40 feet of granite that feels like it is overtaking you like a crusting wave, and 2,000 feet of air beneath you.

My lead up the Great Roof is a memory I will remember for the rest of my life. Working in silence using my headlamp to guide C3 size 0s and hooks into the tiny splitter crack that was wet with moss and water. When Jake arrived at the belay station I showed him a tiny hole in the rock I found, that about 10 drops of water every 30 seconds would seep from. We took turns sucking from this rock pinhole, getting about a half a teaspoon of water (and a mouthful of rock gravel bits) with every turn. We were desperate for water that wasn’t from our rations, and we had to be off the wall by tomorrow or face serious concerns. We must have sat there for 30 minutes silently taking turns trying to squeeze water out of the wall.

I had three pitches to go, it was getting late. I took off through the Pancake Flake and the awkward pitches above. Just shy of Camp 5, and about 2am in the morning I whipped off some flared cracks, bruising my ankle and really spinning out mentally. We had been at it for about 18 hours and climbed over 1,000 feet. Jake jumped on the lead to get us those last 60 feet to Camp 5. We were spent. It was one of the hardest days of my life, I was mentally so fried. But even in my frazzled state, I knew it was one of the best days of my life.

At Camp 5 rushing to set up the portaledge, Jake tripped off the small natural ledge and managed to grab the portaledge’s railing, making a huge trapeze swing into void of darkness. He was fine (and was obviously roped in should he not have caught himself). But witnessing that made me spin out even more. The exposure, lack of food and water, the unknown still ahead of us. Things felt like they were getting dire. At the point of reaching Camp 5, bailing back to safety in case of an emergency starts to feel more daunting and challenging then just getting to the top. Above the Great Roof, we had to keep pushing on. With the amount of traversings and overhangs we had overcome for 2000+ feet, a retreat felt confusing, and even dangerous.

We passed out at 3am forcing ourselves to eat, and needing to be up at 7am to ensure we summited the next day. Laying there frazzled, I did something I regret. I had wanted the Nose to be as much a mystery as possible (despite knowing the obvious obstacles and following the guide map that shows the route). But I also knew my two hardest lead sections were above me, one of them being called the “Glowering Spot” that I knew nothing about. With my phone in my sleeping bag, I turned it on to try and google whatever beta I could find. The only search results that popped up were recent news articles about a climber that blew his pieces of protective gear on that section of rock causing him to fall onto the ledge below. He broke both his legs and was airlifted out by rescue helicopter. As I laid there delirious, exhausted, I convinced myself in a few short hours I’d suffer the same fate. Great, I thought, at least we will be airlifted to the Valley floor where I can get a cheeseburger and vow to never again wander more than 15 feet from a source of water. I passed out shortly after.

The next morning we were up early. I cast off convinced I was facing my Tibula and Fiubula’s demise on the Glowering Spot in a few short minutes. I quickly realized I had the chops to get past this delicate section by relying on hooking a completely vertical but nearly nothing flared crack. A couple pitches higher, I had my final crux pitch, the Changing Corners. Jake would then take the final pitches to the top.

Changing Corners is a 5.14 free climb, making aid almost required for nearly every climber on the planet. I leapfrogged Triple Zero C3 Cams that are about half the width of the tip of a pinky finger into this sharp corner system (my one hook I had didn’t fit the tight corner). The day was dragging on with my aid slow going. With no time to test each placement by bouncing a little with each placement, I’d jam the piece in, and close my eyes as I stepped up, as not to have to watch me take the 40 foot whip I was convinced was coming. The wind had picked up and was making crashing sounds on the wall the way big waves sound crashing from far away on the beach. With each roar a gust of wind would rush up around me as though it was pushing me upwards. My aiders flailed like flags but vertically above my head. I stuck each placement perfectly, and before I knew it I arrived at the hanging belay. I had done all the work I needed to do. Jake would be the guy to take us the rest of the way to the top as the sun started to set.

The final pitches felt such a relief. I know Jake had some hard climbing ahead of us (and I could see he was tired) through the alcove and wild stance, but our confidence was high. Holy Shit, we are going to make it. We were completely out of water, nearly unable to talk because our throats burned so badly. At about 8pm Jake disappeared over the crowning cap rock of the wall, and a minute later yelled ‘off belay’! We arrived at the summit to the biggest miracle of all, a half-full jug of water and an old chapstick sitting right at the final El Cap tree finish line. We had done it! 4 attempts, and a 3.5 day final effort to get ourselves up the a wall that for so long I had dreamed about.

We slept well that night. We were up early the next day and down the East Ledges and back to the car by 11am. We had successfully climbed the Nose of El Capitan and were off to the nearest

Mexican restaurant to eat our faces off.

—

I’d like to think I held my 50% end of the bargain. But that wasn’t the case. Jake stepped in more than a few times to keep us on track. And I could tell how hard he had to push himself when the going got rough for us. It was hard in the moment, but a true inspiration and a rare gift to watch. A guy that has the iron will and strength to just keep going. For that I am forever grateful. I got to live a dream, have a blast with a dear friend, and create a memory I will never forget. I hope to repay him in some way down the road on the next adventure.

I came home from that trip and life got incredibly busy for me. I had a perfect daughter born a few months later. I started a demanding job that required travel. For a brief stint I thought that big walls and big adventures were a chapter of my life that was behind me now.

But I soon realized this simply isn’t the case. Yes, balancing the responsibilities of being a parent will forever be a challenge. And no, I do not want to spend 5 days on a wall away from the beauty of seeing my young child, wife and dog every day. But through this process, I realized what my true values are. I want to pursue a lifelong commitment to improving my health, wellness, and fitness and endlessly pursue being outdoors. I want to create those little micro-adventures throughout the busy work week (a morning trail run, a dog and baby walk on the beach, an ocean swim) that provide me a way each day to be in nature and celebrate it. But also for when those bigger opportunities present themselves again, whatever they may be. And mostly, I realize how blessed I am, that I can continue to create, share with family, and celebrate the wild adventures of life, whatever they may be.

I’ve learned that the adventure of life just keeps getting bigger.

The Nose of El Capitan.

Jake and I on the summit of El Capitan the next morning.

Going up the bolt ladder from Texas Flake to Book Flake.

Hauling fixed lines to Sickle Ledge on the lower pitches of the Nose.

Nights on the Portaledge are the best thing about Big Walls.

Jake on Sickle Ledge.

Late night under the Great Roof.

Casting Off for the Glowering Spot.

Evening on El Cap Ledge.

Back on the wall for the fourth time, this time for the send.

Jake on the middle pitches of the Nose.

Morning on Camp 5.

Looking down from Camp 4 under the Great Roof.