In its own inevitable life cycle (whether decades or centuries) , an industry meets the limits of its own design. Efficiency begins to consume itself. Coffee is arriving at that moment, five hundred years of cultivation, commerce, and culture converging on a single inflection point.

The roots of coffee’s power

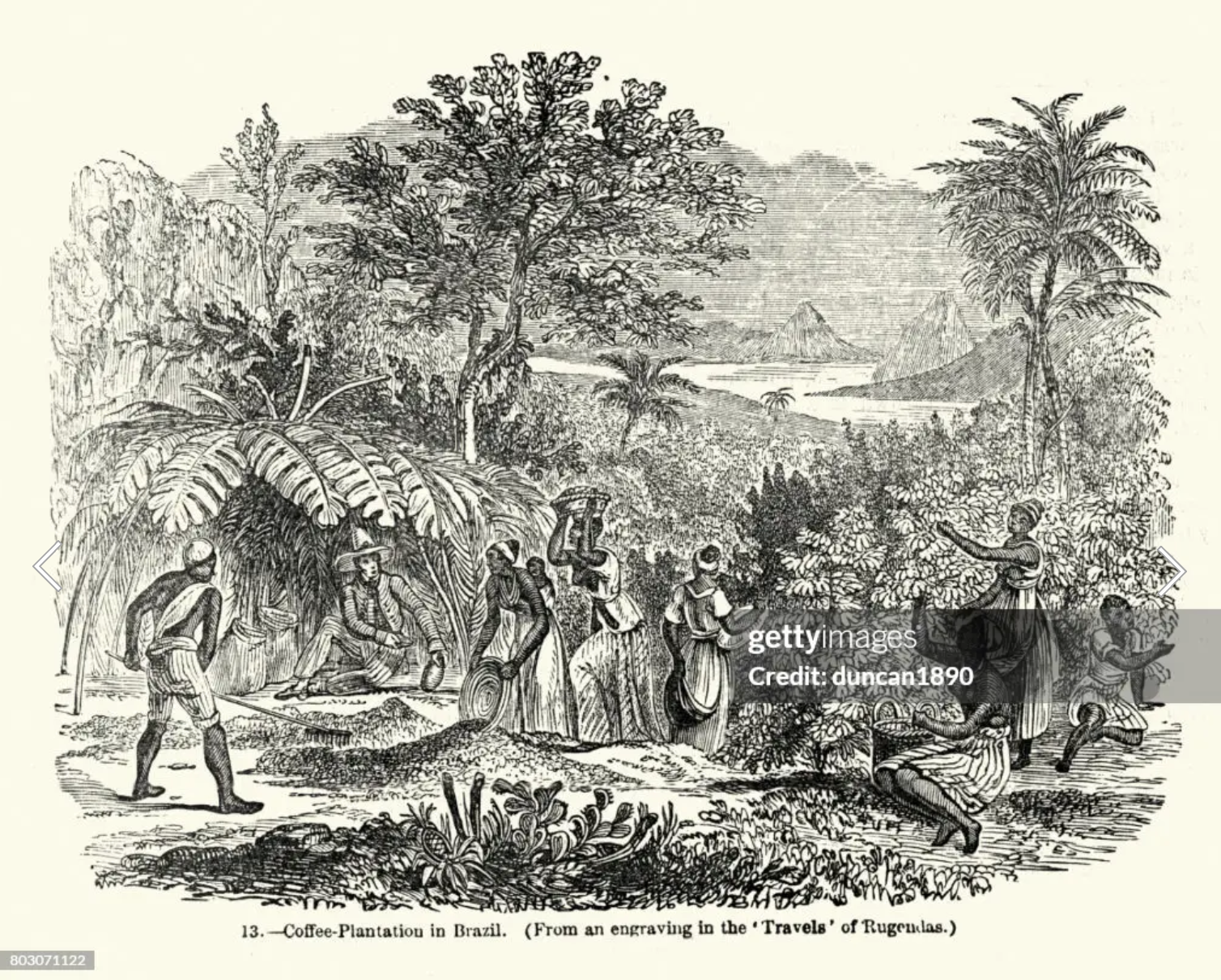

The modern coffee economy was born inside plantation systems built on enslaved labor. In the eighteenth century Saint Domingue, now Haiti, produced vast amounts of coffee with enslaved Africans working in the mountainous interior under some of the harshest regimes in the Americas. The Haitian Revolution upended that order and buyers shifted ever more toward Brazil, which did not abolish slavery until 1888. The people who controlled land, credit, export houses, and state policy carried that power forward. Coffee’s global rise rode on extraction and coercion, and the echoes set the stage for who holds value today.

By contrast, crops like grapes evolved through systems where farmers retained far more market power. Centuries of regional winemaking and direct trade shaped a culture of price integrity and quality differentiation, showing what happens when growers, not empires, define the terms of value.

The past is never far. It moves through our hands, our habits, our morning cups. It lives with us this very hour.

The machinery of efficiency

Over time colonial force gave way to corporate structure and commodity finance. Most arabica pricing still references the New York futures benchmark that the trade calls the C price (note: ICE is replacing this model a bit), with many quality premiums calculated as a differential on top. That means volatility and incentives from the commodity core still shape specialty outcomes.

On the supply side a few producers dominate volume. The USDA projects Brazil around sixty five million sixty kilogram bags and Vietnam about thirty one million for 2025 crop years, with Vietnam remaining almost all robusta. The pattern is concentration and scale.

The agronomy trap

Coffee evolved as a forest shrub. Shade moderates heat, buffers moisture, and invites biodiversity that can stabilize farms. Twentieth century modernization pushed full sun systems to chase yield. Sun systems often rely on more fertilizer, pesticides, and fungicides. They remove canopy that supports birds, insects, and soil life. The result is more volume in the short run and more fragility in the long run. Shade systems consistently show higher species richness and can moderate microclimates that help the plant cope with heat.

Disease pressure keeps rising. Coffee leaf rust has expanded with shifting temperature and rainfall. Many growers answer with more fungicide cycles and higher costs even as climate instability undercuts returns.

The consumer race to the bottom

Downstream the market optimizes for speed, certainty, and price. The United States is the largest single coffee market in the world. Starbucks defines much of that landscape, operating tens of thousands of stores and serving as the model of consistency and efficiency that global consumers have come to expect. Its size and pricing power have trained the U.S. consumer to expect a particular price band for a latte or brewed coffee, even as input and labor costs fluctuate worldwide.

Across the Pacific, Luckin Coffee in China has built a model that mirrors and intensifies that efficiency. With more than twenty six thousand stores driven by app ordering, digital coupons, and rapid openings, the company’s pricing strategy undercuts competitors and has sparked a race to the bottom in urban coffee consumption. In recent months Luckin has begun deploying into the United States with cheap pricing incentives and algorithmic discount systems, forcing Starbucks and even independent specialty cafés to respond. What began as a regional pricing experiment is now influencing how global chains think about market share and discount elasticity. The result is a worldwide race downward that pressures farmers, roasters, and cafés alike.

When the world’s largest and fastest growing markets compete on convenience and price, the pressure radiates backward through the entire supply chain. Consumers get cheaper cups, but the cost is shifted to farms and ecosystems. Distributors push for lower green coffee prices. Producers stretch chemicals, fertilizers, and labor to meet yield targets that hold retail prices steady. Efficiency on the consumer side multiplies exploitation and chemical dependency on the producer side.

It is like the $0.99 two-taco deal that a well known fast food chain uses to get you in the door. At that price you are not really buying food, you are buying a funnel. The company hopes you will also buy the high margin soft drink. The tacos themselves are not the kind of food anyone should want to eat (it’s not possible to bring a taco, let alone two, to market for $0.99, buyer be warned). In coffee the same logic applies. The loss leader is the cup. The pressure rolls backward through the chain, reaching farmers, chemicals, and ecosystems that carry the hidden cost. Food media in China has already chronicled price wars that pushed lattes down to single digit Chinese yuan during promotions. It may look like a deal for the consumer, but someone always ends up holding the bag of excrement, I mean the bill. And its usually not the corporation, but the farmer, the land, or the future generation that pays the hidden cost.

The climate squeeze

Climate change tightens the vise. Multiple studies project that by 2050 global land highly suitable for arabica will shrink drastically, by about half, with suitable zones moving upslope and many current areas becoming marginal. Robusta has gained ground in part because it tolerates heat better (but is still a shrub, so not great), and Brazil is closing the gap with Vietnam in robusta expansion (By the way, robusta is a harsh flavor on its own, its prevalence contributes to conventional coffee’s further bitterness and increased caffeination).

When weather shocks hit, the default response in commodity systems is more inputs, more irrigation, more robusta, and more consolidation. The system that produced abundance loses the ability to adapt.

The singularity moment

This is the singularity. A supply chain born in plantations and refined through commodity finance and software now races to the cheapest possible cup. Sun systems lean harder on chemicals to survive rising heat. Coupons and apps drive price as the governing truth. The system keeps cups cheap by externalizing ecological and human costs.

The lab grown fork in the road

Another piece of this singularity is the capital pouring into synthetic and lab grown coffee. Researchers in Finland documented a proof of concept for cell culture coffee and published a process overview. Venture backed companies are scaling beanless formulas and ingredients. Atomo announced new funding in 2025 and claims large water and carbon savings per cup. Compound Foods is now supplying lab-grown coffee ingredients to other companies, positioning itself as a buffer against volatile supply chains. This is not science fiction. It is happening now.

There are tradeoffs. If synthetic options capture share, millions of smallholders may lose markets. That is not only a social hit. Or a way of life and culture hit. It is also a climate hit. Coffee agroforestry sequesters carbon in trees and soils and supports biodiversity. If economic value detaches from living farms and moves to labs, we lose livelihoods and we lose the carbon bank that shade coffee and even sun coffee partially represents. Even advocates acknowledge the need to confront the livelihood risk.

My position is clear. Innovation has a place. But a future that sidelines farmers and forests misses the point. We need farming systems that work for people and for living landscapes. And isn’t it just more delightful to know your coffee was grown with the rhythm of the seasons, shaped by the rains, picked by hand, by a far off exotic sounding place?But I digress..

What comes after the singularity

A better path looks like agroforestry and permaculture rather than bare sun. It looks like traceable and transparent trade rather than anonymous lots tied to an exchange ticker. Studies show shaded systems store more carbon and support wildlife while buffering heat. Some work even finds that medium shade can align with strong productivity at the right elevations and management. This is not romanticism. It is a practical design for resilience.

It also means broadening the genetic base. Arabica and robusta will remain giants, but the world is beginning to rediscover the liberica complex, including Excelsa, which has now been recognized as its own species. Excelsa is the wild one. It thrives where arabica fails, tolerating heat, drought, and challenging soils. It grows best in diverse agroforestry systems (it is a 30 foot tree, with larger leaves, and a deep root system after all), rather than in sun exposed monocultures, and it carries a flavor profile unlike anything else. The taste is deep, fruit forward, and slightly wine like, naturally lower in caffeine, and often chemical free by its resilient tree-like nature rather than just marketing.

Recent genomic work confirms Excelsa’s distinct specie lineage within the liberica family, and field research continues to show its resilience in the face of a changing climate. To me, Excelsa represents what the future of coffee could look like. It is diverse, adaptive, and aligned with nature instead of fighting it. I’ve witnesses this in my travels: fragile pesticide smelling arabica and robusta shrubs suffering in the sun, neglected excelsa trees thriving on the farm’s outer parameter (let’s work on those!). A diverse coffee future is not only a hedge against a hotter planet, it is also an invitation to rediscover what coffee can taste like when it is allowed to stay wild.

The consumer’s role

Yes this path costs more. That is honest. The good news is that a meaningful share of consumers will pay premiums for sustainability. Products marketed as sustainable and regenerative have delivered an outsized share of growth in consumer goods. In other words the market signal is real when the offer is credible, and the conversion from shrub to tree is an easy visual sell.

There is also taste. If you care about what you put in your body you already know that taste can be trained. Coffee is a bitter beverage and bitterness is complex. During roasting, chlorogenic acids break down into compounds like lactones and phenylindanes that shape bitterness, and our perception adapts with exposure and context. The science on acquired taste is clear. Repeated exposure can increase liking, and genetics and experience both influence how we perceive bitter drinks like coffee and wine.

Here is my personal note. I switched to excelsa last year. The palate adaptation took time. Now I cannot go back. Last week I had to wake very early and grabbed a Starbucks on the road (I was hesitant but needing to make a long drive on little sleep). All day I could not get the taste out of my mouth. It tasted bitter and chemical and burnt. Wild coffee tastes living and layered to me now. More earth. Less of the synthetic edge that sits under the race to the bottom. Taste is not a small thing. It is the direct interface with our choices. It can change.

If you prefer a simple design language for life and pantry there’s a name for it in Japan. Kanso. Simplicity and intentionality. Fewer things of higher integrity. Apply that to your cup. Paying the real cost for something honest is always worth it.

The final thought

The old model is a collapsing star. It burns bright and cheap by consuming itself. The post singular model is slower and more intentional. It restores shade, protects farmers, and delivers meaning and flavor. We do not need everyone to switch. We need enough people who care. That is where excelsa and other diverse species grown in agroforestry and traded with real transparency can help build a better coffee economy one cup at a time… proving that a system built on care can serve people and planet for the next 500 years.

HTML source links

Smithsonian: Slavery and coffee in Saint Domingue

Oxford Research: Abolition of Brazilian slavery

Brown University: Brazil coffee chapter

Specialty Coffee Association: C market and differentials

USDA: Brazil Coffee Annual 2025

Smithsonian Migratory Bird Center: Shade coffee

Frontiers in Sustainable Food Systems 2022

Luckin Coffee Q2 2025 financials

FoodTalks on Chinese price wars

World Coffee Research: Arabica suitability 2050

Reuters: Brazil robusta expansion

VTT Research: Lab grown coffee concept

Atomo Coffee: Funding and claims

Compound Foods: Ingredient platform

World Economic Forum: Risks of lab coffee

Frontiers in Plant Science 2024: Carbon reserves

Nature Plants 2025: Liberica genomic delimitation

NYU Stern Sustainable Market Share Index

McKinsey and NielsenIQ: Green product premiums

Scientific Reports: Bitterness and coffee intake

PMC: Phenylindanes in brewed coffee

ScienceDirect: Acquired taste study